Breadcrumb

María Carolina Ceballos Flórez

Cantos

Performing arts and their notation in relation to the book arts:

A creative research project for un-common convergences.

María Carolina Ceballos Flórez

Books have been used as tools for singing for a long time. Neumes, for example, were used by medieval monks to give certain intonation and unity to prayers recited in group. Books have recorded music and other performative arts in a silent space, a space different from a CD or a vinyl record, where our bodies create the sounds or movements, where the record’s speaker is, indeed, a human body that activates symbols and images engraved in objects and paper.

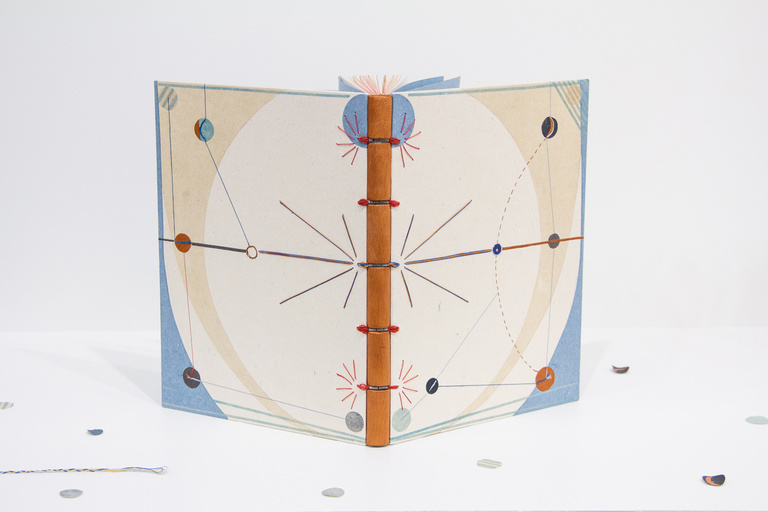

Books, then, need a human body to perform themselves, but books have their own body too. A spine, a weight, layers of skin and bones protecting the tripa, cords like nerves, paper that speaks by itself, and, finally, memories in the shape of symbols, like a dormant brain, whose neurons are the electric movements and waves of our body interpreting them.

These symbols have become standard, like languages or manners, as music writing evolved with the evolution of music itself. But, what happens when these standardizations are questioned?, when English and Spanish interwind each other like thread; when a quarter note has as much significance as the shape of a leaf; when to go through the book means to make sounds, songs or dances? I question symbols and objects to perform beauty and for the book to be beautiful, to let you learn that new language – with mistakes and misconceptions, with your own intuition –, to re-think the book’s body as an extension of our own.

Words mean different things depending on their container. We know that. When singing words, we make them, in a way, sacred. As I sing, let’s say, a choral arrangement of a poem, I can feel, not just that silent and individual voice of the poet, but the movement of the hands of the composer playing the piano as he or she interprets the poem in their own language of music. Seems like music had made this poem a universal truth. Now we all hear the poem in a similar way. Now we all feel, with so many different colors, shades and paces, the same.

Writing my own songs or painting my own graphic scores from my poems is also a way of setting a specific path for feelings –the same way monks would write symbols over sacred texts so you can hear the same feeling, and so they can all, together, sing it.

Singing my songs, in Colombian rhythms, feels to me very different from reading the music sheets for a choral arrangement, or reading and almost reciting chants with intonation but not tempo in the Gregorian notation. In a choir, I read with my ears and the tip of my eye the voices and bodies of others, and they do the same, in the invisible dancing that is singing in community. But we don’t just sing with others; we also sing with the score, the score speaks to us in very specific ways, color coded or not – like medieval manuscripts –, hand written, engraved or type set, in a pocket sized book or in a huge heavy manuscript: the book is telling us how to read from it, how to interact with its materiality, what to say or sing and what to keep to ourselves, as if the chorists had a secret friendship with the book, as if the ritual of singing from a book was, indeed, sacred.

This relationship I have with singing and music notation has awakened, in the last years, a question about these ways of communication, and how much we can challenge the action of performing and the craft of bookmaking to intertwine them in all possible ways.

This is nothing new, many have done it, since, from the beginning, we look for visual aid to our performative acts. This research looks for the past key moments of the evolution of this matter, while looking forward to future/in progress pieces that experiment with different approaches to it.

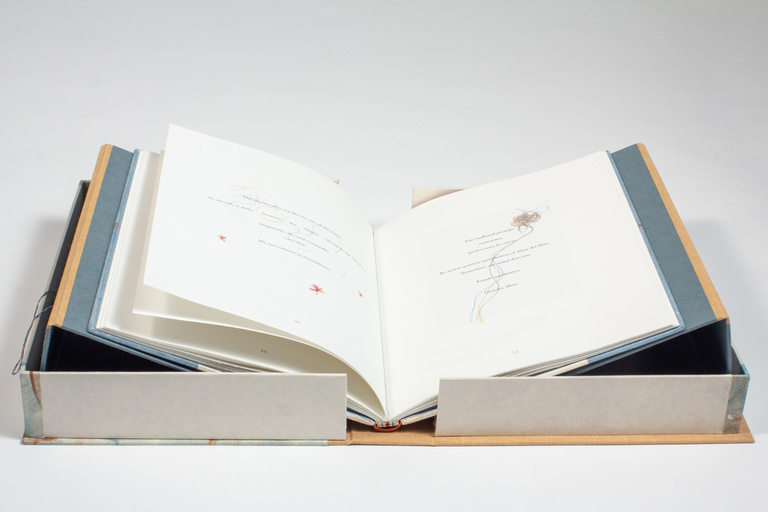

Cantos is a compilation of two books created as an output of this research. They were made as odes to my bookbinding and papermaking practices, both refined during my time at the University of Iowa Center for the Book.

The books are two different approximations of what a graphic score can be in relation to the characteristics of a codex-like book and the performance possibilities or the openness of this kind of notation.

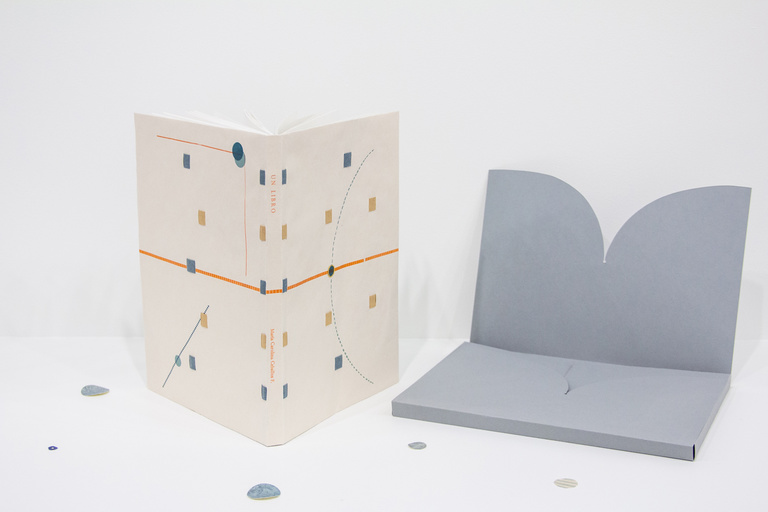

Canto to the book crafter: Un Libro

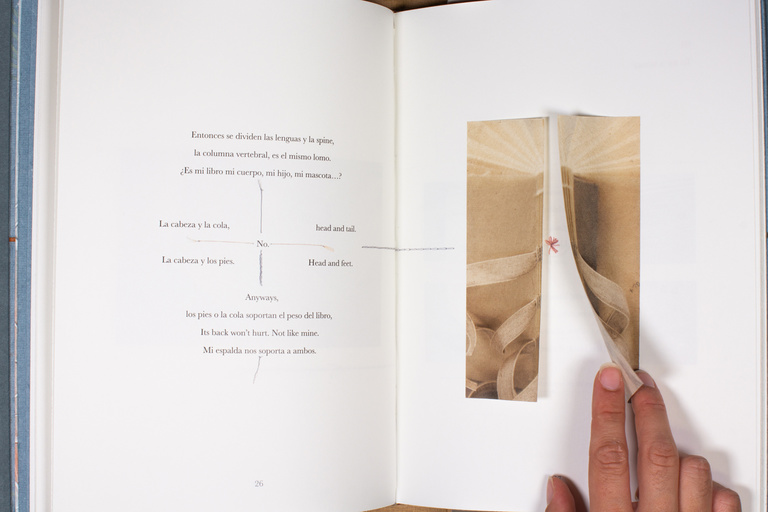

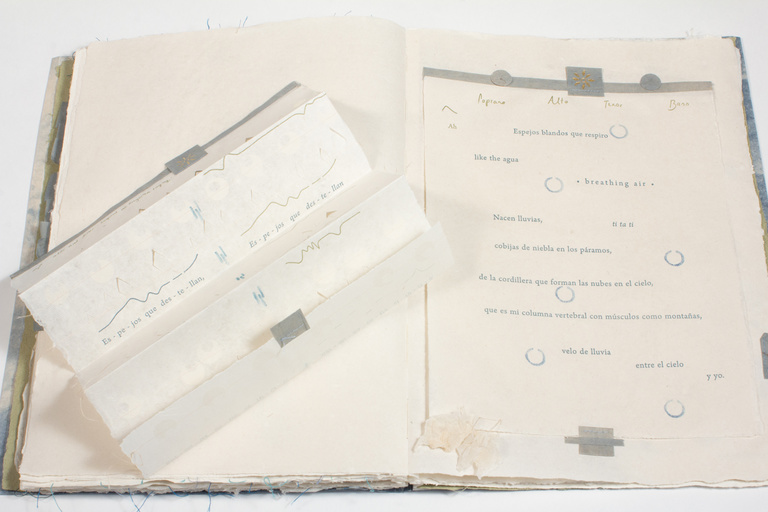

Un Libro has its own language. In the shape of a book, the printed content explains that book with words of my own, with lines of thread, pieces of paper, and lines of text made with pieces of languages.

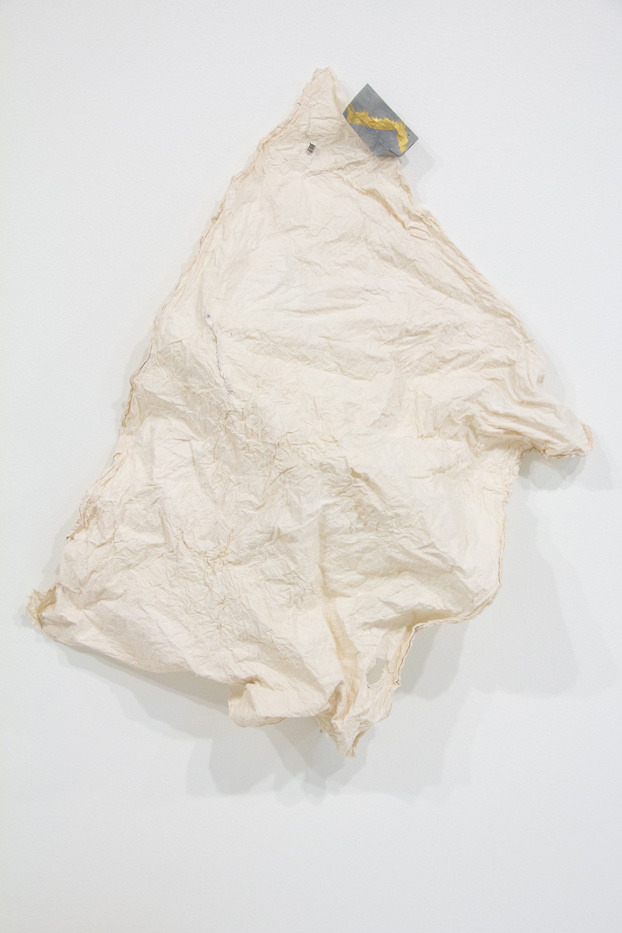

There is a performatic act when crafting something, in this case, a book. The book connects with our body by its craft but also by itself. To name a book and its parts is to recognize ourselves in it, its body is a mirror of ours.

As a woman, the body of the book becomes both my own and something like a baby’s. I created it, I have to take care of its materials and words. The time spent on its creation resembles the time we spend taking care of our bodies, or the time of gestation.

Books, too, age. As the daughter of two physicians, the job of a book conservator is my way of taking care of others. I take care of history, memories, imagination and knowledge; all coming from the human body, all engraved in books that, too, live in time and degrade in their many layers of materials.

This book is an ode, hymn, canto to both the bookbinder and the bookbinding process. It is a song I wrote to myself, my books, my fellow bookbinders, my instructors, the old books I’ve appreciated and taken care of in the conservation lab, and the books I will repair, make and see in the future.

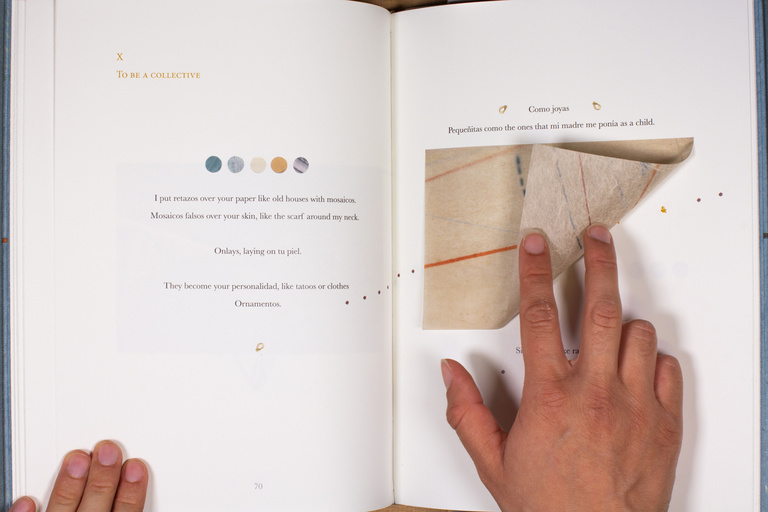

In terms of performance and notation, this book translates the fineness of the thread to the lightness of dancing bodies and voices – bodies representing the book’s, mine, or the antagonist of this tale of stiff bodies –, creating free scores that can mean so much, as well as be abstract lines free of interpretation. The hybrid-language writing translates too to a fluent constant shift in the interpretation of words, for some harder than for others; this understanding of language and craft sets the level of interpretation. As I read it, out loud, I become the body of the book too, it is alive as I pass its pages between my fingers. Photography too becomes the registration of craft the same way other’s bodies are registered by our eyes, so light, malleable and ephemeral and, on time, so abstract: to be photographed is to become an image of the past that does not pretend to endure history, but to remind us of the unknown.

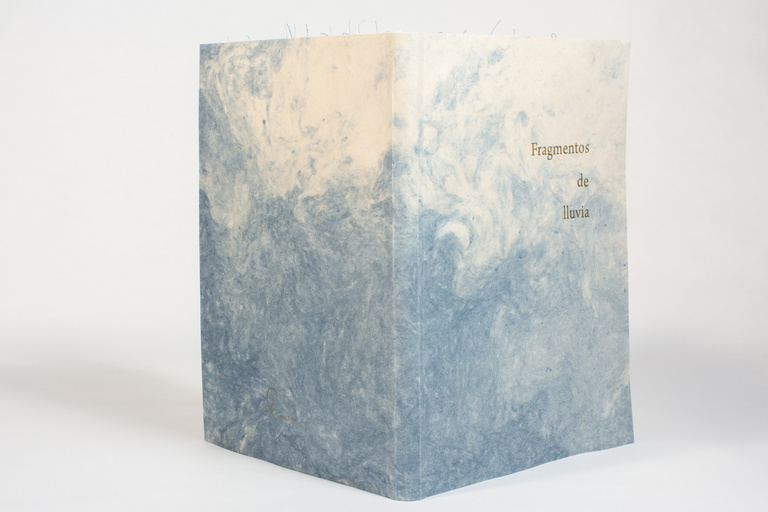

Canto to the water: Fragmentos de lluvia

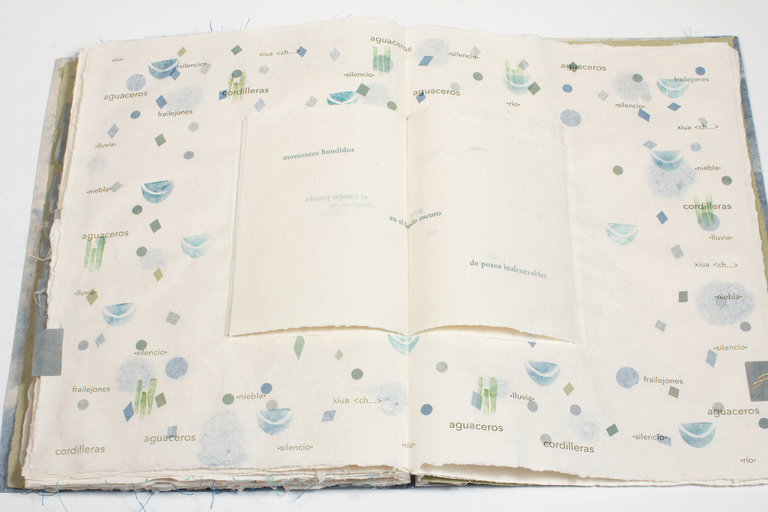

Fragmentos de Lluvia is the second book I made for my thesis. It is an ode to my home and its rainy weather, and how everything in the country depends on rain. It is also an ode to the papermaking practice, a discipline that depends on water, time and rhythm for its creation.

The poem for this book is a compilation of memories of rain and other water phenomena from Colombia, in contrast to my experiences of water in Iowa. Constant humidity and mountains are the two things that stand out from this poem as opposed to the flat dry and snowy Iowan landscape. As the writing evolves, other memories and political concepts come to mind, like violence against humans and ecosystems in Colombia, belonging to the 2nd movement El frailejón, in which I introduce some notions of canción protesta.

This poem became a music piece very quickly, as water and memories flow like music, as my memories of rain and experiences of water with papermaking, both have sound as their principal component. In this way, sounds made with voice and paper instruments complement and illustrate the poem, and it itself flows in a sung recitation that allows both the choir performers and soloist to improvise and move like water does.

As David Rothenberg says in his introduction to The Book of Music and Nature: “Music could be a model for learning to perceive the surrounding world by listening, not only by naming or explaining.” In this case, that learning experience comes not just from the audience listening to my piece, or the performers interpreting it, but also from my own experience of having acknowledged my country’s natural landscape to understand its dynamics and make it part of my memories and main language when writing about home.

The decision of making this piece a choral composition, is because some of the best memories from my life before Iowa are from my choir experience. As I mentioned before, singing in group requires a constant flow between the self and others. Listening is a big part of singing in a choir, since one is a consequence of the voice of the other. Fragmentos de Lluvia is, therefore, a portrait of this idea, in which the very loose and improvisational graphic score leaves much to the group of voices to listen to each other and enter in the right moments based on this flowing awareness of community.

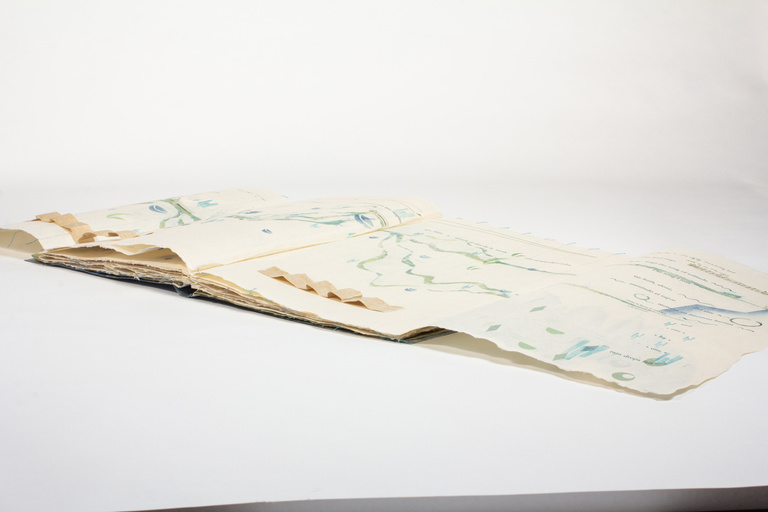

Visually, the scores are paintings made with geometrical or organic shapes that represent sounds, like any other score, but this time in a new language devised by me, with the intention of keeping the visual and material appeal while communicating a notation that is, in many ways, improvisational. Circles represent breathing, like lungs open and close proportionally; leaf-like shapes are whistles representing birds, cause both birds and leaves leave trees by flying away; lines mean melodies flowing like lines in the water of a river.